Chris Kwan delves deep into the legalities of Joint Venture Agreements (JVAs) and what you should be aware of if you’re thinking of entering into one with a property developer or a landowner.

The fact that a contract is titled as a “Joint” may deceitful as it is anything but joint in terms on how both parties work together.

In fact, there is a specific clause that says there is no partnership. JVA’s are very common especially for property development and the term “Joint” actually refers to the outcome and not how the parties related to trust and fairness to each other in particular when there is an imbalance of influence or power which is normally contracted in this JVA.

Typically, a JVA usually involves a developer with “some” cash and a landowner with land and without means to get cash. In most cases, this is a rare find as the land must be free of any encumbrances and its location is attractive enough to see demand for houses or commercial properties. Unless the landowner is facing some financial difficulty, the landowner is usually in a very good position to negotiate or even sell the land if he so pleases.

One may think this is a marriage made in heaven where the developer is the husband and the landowner as the wife but in reality, like any relationship, it pays to be wary with whom one is sleeping with. As in all courtships, the developer will come bearing gifts and promises to vow the landowner. This is not to say all developers are hustlers but in all trades, there will be some bad apples.

This article is about knowing the trade of property development and how to protect one’s interest by way of this JVA. This JVA will normally be drafted by lawyers for the developer and the landowner will have little say unless he or she is willing to hire a lawyer to go through the fine print. Not all JVA’s are biased but unless one is aware of the entire process of property development then one should be particularly wary of its companion document, the Power of Attorney.

Power of Attorney (“POA”)

This document can be found separately or within the JVA itself. Basically if you are the landowner, you should never give any Power of Attorney to the developer.

This is because with this document the developer can leave you out of the loop when it comes to obtaining approvals for all plans from the authority. In law, only the landowner is entitled to deal with the local authority in matters of plans and because of this the developer’s lawyers will draft a very wide Power of Attorney.

In all instances, the power to sell the developer’s entitlements is also stated in this Power of Attorney.

A few issues to note here is to see whether there is a clause that says “the donor of the power agree to ratify and confirm all that our Attorney shall lawfully do or cause to be done”. This means that the donor of the power will only ratify lawful acts which is another way to limit the donee abusing this power.

It is important also to attach a “sunset” clause to this power of attorney so that this power will be extinguished when certain conditions are not fulfilled within a time frame.

It is also common for the developer or donee to get an “irrevocable” power of attorney. It is very foolish to grant this “irrevocable” as it basically means you have given everything up to the developer. There is no requirement for this “irrevocable” power as basically a power of attorney is to allow the developer to do things or acts that should be done by the landowners (donor).

As this is a joint venture and not a transfer of rights, there is no requirement for “irrevocable”. There is nothing wrong for the landowners (donor) to apply to the Local Council and to do what is necessary for the joint venture to be successful.

To put all your trust into a joint venture partner is foolish and fool-hardy as everything that is needed to be done should be known to you or be consulted as donor and consent be given before the developer (donee) actually commit.

Also, never give any right or power to the developer that includes loans or using the property as collateral and have this stated in the Power of Attorney if you must give one.

Another point is the sale of the developer’s entitlements, make sure this Power of Attorney states that the developer has no right or power to give consent or endorse the sale on behalf of the landowners.

Developer’s Entitlements

As with all property development, the reason for the developer to get in bed with the landowner is so he or she could flip or sell their entitlements. Be very careful here as in most cases, the developer will ask that their entitlements be sold as soon as the local authority approved the “building plan”. This is known as selling off the plan.

But in developed countries, the banks will only finance the development when 90% of the Lots are pre-sold. As for developing countries like Malaysia, there is no rule at all, the banks will finance off the plan and take the land owner’s land as collateral for each Lot. However, when it comes to apartments (“parcel of air”) this would be challenging.

The banks can impose this restriction as the developer has a power of attorney to act for you in using your land as collateral.

Therefore it is very important for the JVA to state very clearly that the land cannot be encumbered whatsoever. Another reason not to give the developer their entitlements straight away is because they have not done anything yet to deserve this other than executing the JVA and POA and getting the building plan approved.

The better way is to make sure, as a landowner, you received your entitlement first.

Land Owner Entitlements

For many landowners, they do not have the means and know-how to develop their piece of land and therefore dependent on the developer. The goal here is to get their entitlements first. Usually, the ratio is 1 in 3 or even 1 in 2 depending on the saleability and type of property for sale. It is very important that the landowner also obtain both Certificate of Practical Completion (“CPC”) and Certificate of Fit to Occupy (“OC”) from the developer and or its architect as proof that the project is completed before they received their entitlements. This means the JVA must state very clearly when both documents are expected and the consequences of delay.

I have seen attempts by lawyers acting for a developer to issue other documents arguing these are equivalent to blindside the landowner into accepting the project is completed. The landowner must be very cautious here as a project is not completed until the Architect says so by issuing this CPC and the local authority issued this “OC”. Both are needed before the landowners can officially select their entitlements and accept from the developer.

It is also important for the landowner to state very clearly that they have a first of right to select their entitlements before the developer to ensure that the developer has actually completed the whole project.

How Developers get around the above

It is common for developer to include a clause in the JVA that says that in the event they cannot complete the entire project, they will pay an amount calculated now to be banked or guaranteed so that at least the landowners’ entitlements are completed. In short, the developer is arguing the case that there is nothing to lose as the landowner will get their entitlement even if the project failed.

In theory this is correct but in practice, this is an affront to any intelligent person. In the event the developer cannot complete the project (due to bankruptcy) the funds will be insufficient as much be needed to pay off outstanding first before work can be resumed. Secondly, the local authority and architect could not simply issue certificates for “part” of an incomplete project. This means while the Lots are complete in terms of work or labor, no certificates could be issued and hence there is no value in those entitlements.

Developer will also sell off the plans to related entities to get financing. The banks will lend money to the borrower and pay off the developer on a schedule of work completed. As I said above, the developer can execute the sale and purchase agreements due to the power of attorney, so it is very important then to either make sure that all sale and purchase must be endorsed by the landowner (stated in the JVA) and to exclude any sale and purchase from the power of attorney save where consent is given by the landowners.

There is no reason to allow the developer to have exclusive power to sell without your knowledge as this is a “Joint” venture. This is not to say landowner is preventing the developer from selling its entitlements at all, rather landowners should be at the very least be informed. This right to be informed is very important especially as most sales are finance dependent and the bank will only accept land as collateral.

Developers may also entice the landowner with a smaller scale project using less land but after the JVA and POA are signed, submit a different plan to be approved by the local authority. The only way to get around this is to make sure the POA is limited here and in the JVA says very clearly that all development plans must be approved by the landowner or to make sure the Architect is responsible to both landowner and developer. This is very rare as the architect is normally hired by the developer and listens to the developer.

So before getting into bed with any developer make sure the Architect is a reputable one. Have a chat with the Architect and asked him to sign separate agreement with landowner that reflect he is also responsible for the interest of the landowner.

In most development, local authority would require some “infrastructure” to be included such as roads, sewerage, drains etc that would require more land beyond that was initially agreed to in the JVA. The local authority may not approve the development unless this is agreed and this will be in the form of “amendment” to the development plan (after the initial approval). The development plan is not a ‘static’ document and is subject to amendments from time to time.

The landowner should be very careful here as the developer will use his POA to agree to the local authority and give up more land than agreed in the JVA without the land owner’s consent. The developer will argue that this is a requirement and he or she has the absolute authority to use the land owner’s land for the development and to seek all approval as he or she sees fit.

In a recent case in Sabah, the learned Judge had argued that the local authority has such as right derived from the ‘reserve road’ having been demarcated in the Local Plan and also drawn on the development plan even though no consent was obtained from the landowner. The learned Judge reasoned that the landowner has been “compensated” although I don’t see how in return for approving the project is within “adequate compensation” as required under Art 13 of the Federal Constitution. It is also a dangerous precedent as it overcomes the objects of Land Acquisition Ordinance.

Fiduciary relation and good faith in Joint Venture Agreements.

This is perhaps the most important protection and in most cases over-looked. A duty of care is owed by the developer to the landowner as the law recognised the unequal relationship in the High Court of Australia case of Jenyns v. Public Curator (Q.) 90 CLR [1953-54] 113 Dixon CJ, McTiernan, and Kitto JJ have this to say at p. 133:

“We are not here dealing with any of the traditional relations of influence or confidence -solicitor and client, physician and patient, priest and penitent, guardian and ward, trustee and cestui que trust. It is a special relationship set up by the actual reposing of confidence. It is therefore necessary to see the extent and nature of the confidence reposed and whether it involved any ascendancy over the will of the person supposedly dependent on the confidence.”

Similarly, reference can also be made to Australian Supreme Court case of Brian Pty. Ltd. v. United Dominions Corporation Ltd. [1983] 1 NSWLR 490. Samuels JA at p. 506 says that after reviewing the authorities, he is of the opinion that joint venturers owe to one another the duty of utmost good faith due from every member of a partnership towards every other member.

In Malaysia, I can do no better by referring to the leading case is Newacres Sdn. Bhd. v. Sri Alam Sdn. Bhd [1991] 1 CLJ (Rep) 321 and I quote “The Judges here were talking about fiduciary relations between the parties.” referring to the above cases (at page 332 para e). “We would, with respect, accept this proposition which goes to show that if the agreement of 2 October 1980 entered into by the litigating parties is indeed a joint venture agreement then their relationship is a fiduciary one.” (at page 333 para a-b).

But this may not be as simple as merely labelling your contract as a Joint Venture Agreement. The opposition may want to argue that not every Joint Venture Agreement must ended up with a fiduciary relationship, some may not be at all as given the scope and terms agreed upon. To check whether “property development” type of Joint Venture falls into this category, we need to observe and decide whether the terms of the contract is to pursue a mutual aim – one in which each of them has an interest – the situation is likely to be very different.

The terms will need to express a dependence with each other, place trust and confidence in the other, to cooperate to achieve the outcome to which their contract is directed, and to do so for the benefit of each. In the case of Adventure Golf Systems Australia Pty Ltd v Belgravia Health & Leisure Group Pty Ltd [2017] VSCA 326 [188]), his Honour reinforced this “joint interest” by saying “Although, no doubt, each party has its own individual and legitimate interest in entering into the bargain, the bargain is one not merely for the achievement of that interest, but also for the achievement of the joint interest. That, I think, is one reason why parties to a contract that may properly be described as one of ‘joint venture’ have been found to owe fiduciary obligations to each other.”

Having fiduciary relations means that your joint venturer must not exploit you in law for his benefit only. Again in Adventure Golf Systems Australia Pty Ltd v Belgravia Health & Leisure Group Pty Ltd [2017] VSCA 326 [120] said and I quote:

“The essence of a fiduciary relationship is that one party to the relationship is obliged to act in the interests of another party (or, in the case of a partnership or joint venture, their joint interest) to the exclusion of the former’s self-interest. As a result, the fiduciary is prevented from entering into any engagement in which the fiduciary has, or could have, a personal interest conflicting with that of his or her principal; nor is the fiduciary allowed to retain any benefit or gain obtained or received by reason of or by use of its fiduciary position or through some opportunity or knowledge resulting from it.”

In conclusion, parties should be wary of how the terms were agreed upon as stated by his honour “More often than not, commercial transactions which were negotiated at arm’s length between self-interested and sophisticated parties on an equal footing do not give rise to fiduciary duties.” Ibid [125] and in most cases may not be “automatic” as suggested rather a detailed factual inquiry will be required in each case where parties seek to establish fiduciary obligations within a joint venture framework.

Generally other clauses are standard in all other contracts such as everything within the four corners and pre-negotiations are excluded. This goes beyond issue like contra proferentem.

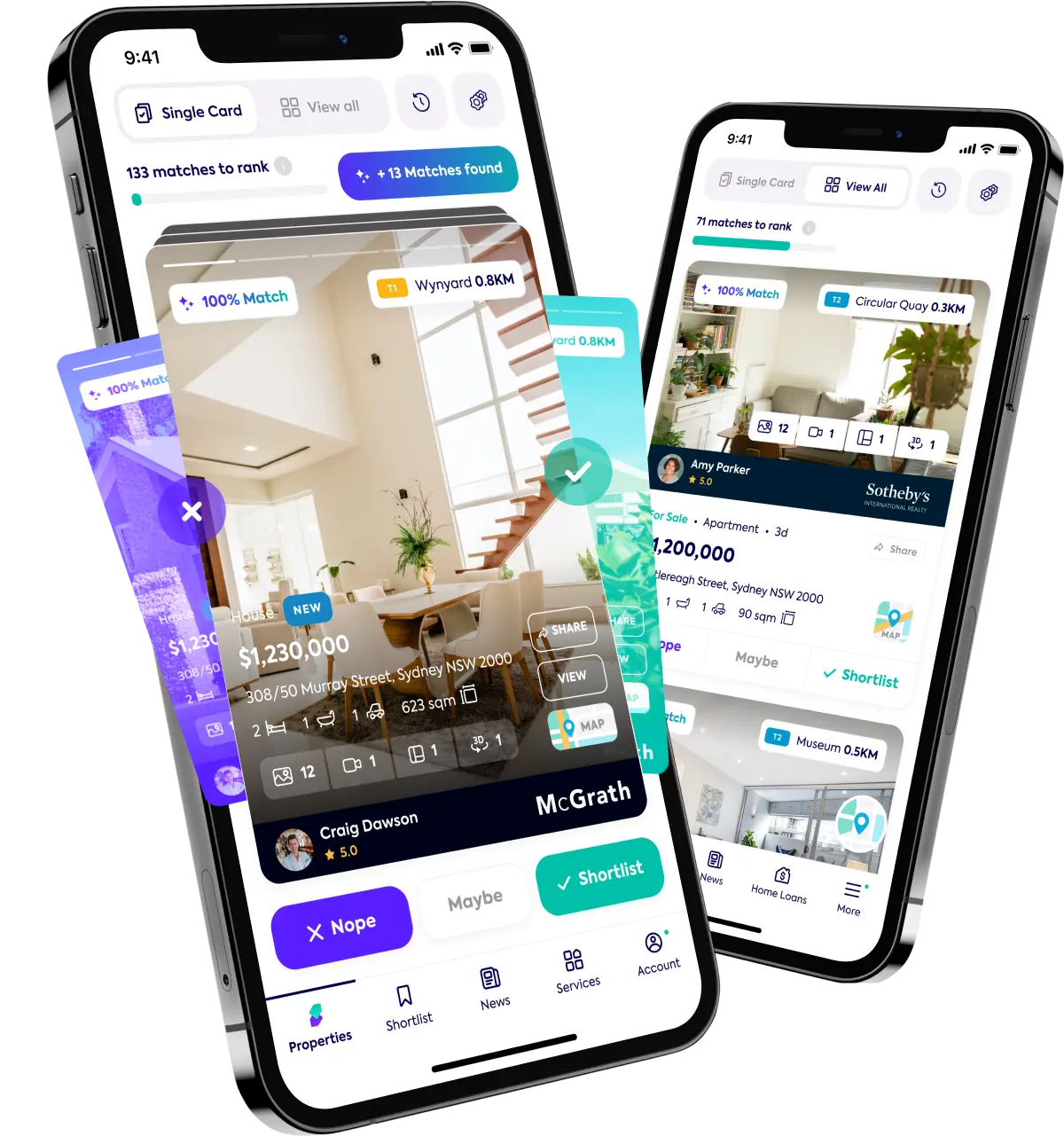

Looking for your dream home?

Soho can help you find it. Set up your profile on Soho to find properties for sale and properties for rent in your favourite suburbs. But don’t just stop there, download our app to get access to more features. Just remember to shortlist or swipe left on our listings so we can send you others that better match what you’re looking for.